The closer we move to our time, the more evidence has survived — and the more elbow grease has gone into studying it. This book isn’t a research paper; it can only point a finger and ask real scientists to look “over there.” At least until Alex gets his “funding.” If any real scientists are reading this — please, look “over there.” Who knows, maybe there’s something interesting in that direction.

The Navel Religion

The niche carved within society for the spiritual overlaps surprisingly strongly with scientific and engineering disciplines. It might be association by negation — both, at their core, focus on improvement and creation, not zero- or negative-sum games. There’s no reason to expect otherwise from the humanities of the past.

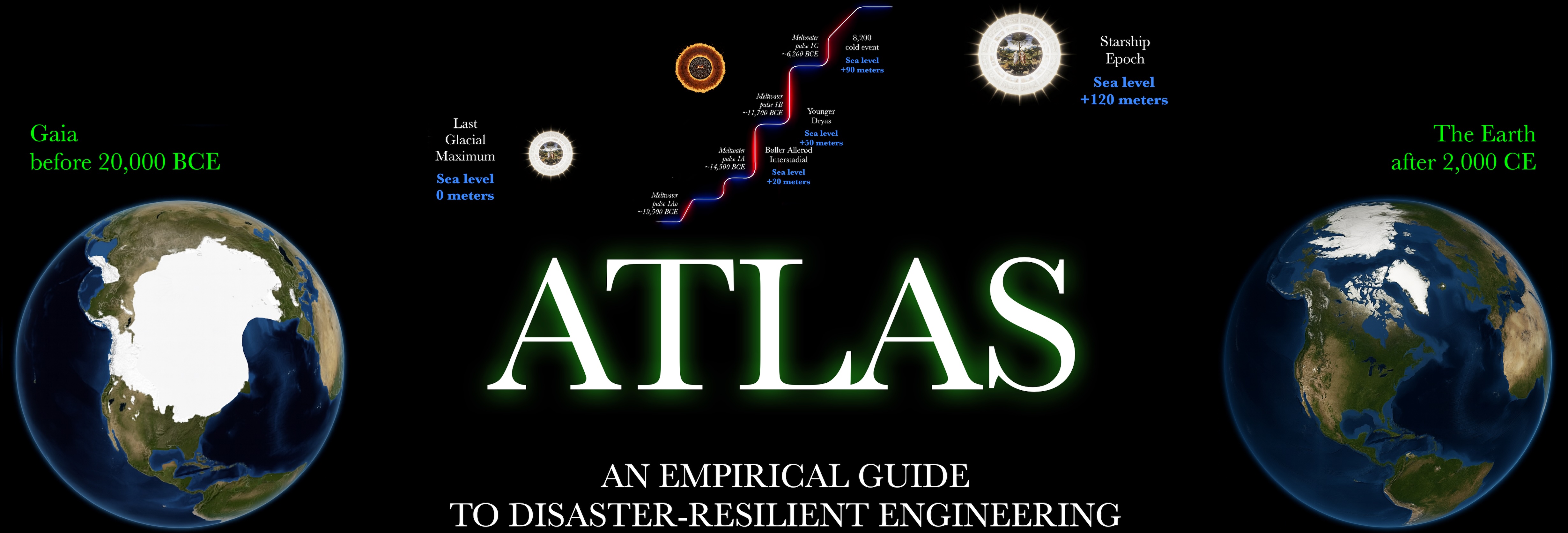

As this book has shown, since the fall of the Golden Age, every scientific effort on this planet has been restarted by the “engine of civilization” — Atlas.

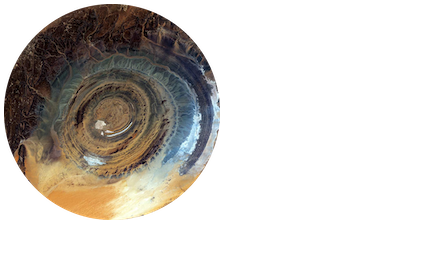

But what about places beyond the vicinity of Richat? The chain of “Navels of the World” encircled the planet. There may have been other space elevators. The Cardinal Quartet of the Sons of Horus or the dwarves could have been free-standing structures, disconnected from Atlas — at least initially. Or Atlas itself might have been detached and moved to another tether dock, stopping only when it was crippled.

Whichever the case, the light of civilization was associated with the places from which it spread — the docking stations. And, as we’ve seen, they loved comparing space elevators to umbilical cords linking Earth and sky, and called their docking stations “Navels.”

Just as we associate the monasteries of the Dark Ages with contemplation and discovery, during planetary upheavals, science and engineering must have taken a back seat to simpler practices — ritualized obedience, symbolic signs, and carvings in stone.

The number of statues worldwide holding their navels is staggering — immediately, the Rapa Nui Moai and Göbekli Tepe, separated by ten thousand years, come to mind. This gives us a lower bound on the lifespan and spread of this religion. Geographically, we can be sure it was global — assuming the hypothetical space elevators connected every docking station along their equator.

This section is brief, but there’s little more to say without fieldwork — dating the navel-holding statues, analyzing the local folklore. That’s what will give us a volumetric, living understanding of this fascinating ancient religion — and possibly, still existing today.

Note: another remarkable tradition is that of the “animal holder” — a figure gripping a snake in each hand, or sometimes another creature.

Atlantis

At least four cultures are known to have shared a strong conceptual package around “a place of reeds”: Aztec, Egyptians, Bantu, and Oromo. It’s the consistency of context and meaning that lets us calibrate the reality behind the idea so precisely. They share the same tightly bound elements:

- place/fields/mats of reeds — all four

- association of the place of reeds with creation or renewal — Bantu and Oromo

- the “primordial mound” — Egyptians and Oromo (the Oromo count seven years spent within the hill)

- a tall structure rising from it — a lotus, mountain, or reed — Egyptians, Aztec, Bantu

- a sense of being “the Navel of the World” — Aztec (explicitly, in their city’s name), Egyptian (functionally, as the Benben), and Bantu (functionally, as the Uthlanga “source”)

“The Navel of the World” should be a giant red flag by now — it’s always a docking station in this hypothetical universe. And thanks to these cultures, we can infer that it stood amid marshes overgrown with reeds.

That’s already a strong start — three still-living cultures (Bantu, Oromo, Nahua/Aztec) and one foundational ancient one (Egyptian), which we can study — and even interview — to reconstruct traits of the “Mound of Creation” and the space elevator above it.

But it gets better. When we hear Plato say Atlantis, it sounds like a language isolate. And it makes sense: in his story, both Egypt and Greece were founded by the same goddess, while Atlantis — an aggressive empire — sought to conquer them. Despite sharing the same Primordial Mound, they had probably diverged by then — linguistically as well.

The language of the lost empire could have been close to that of the Aztec — a language still partly alive today: Metztli (Moon) + Xictli (Navel) + -co (Place). Get it? This cosmological name, Mexico, confirms “the Navel of the Moon” — the name we’ve heard so many times associated with the Richat Structure — and the Metztli (Moon) part encodes the familiar motif of the Moon or Sun atop the sacred mountain, lotus, or tree — the same archetype of an umbilical cord connecting a luminal object in the heavens. (This is also where the eagle fighting the snake on the cactus — the same concept seen, well, everywhere — fits in.)

The Aztec called their homeland Aztlan — “Place of Herons”; but in their language Tollan means “Place of Reeds.” The Bantu origin place, Uthlanga, also means “Place of Reeds” — the sound is similar.

That’s a lot of threads to pull — absurd, given the completely different language families — yet they’re not vague mythological lore from mistranslated ancient texts, but solid, accessible sources — some still living traditions today. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll look for some bored but talented archaeologist out there, point my finger at the whole mess, and ask that brave real scientist to “look over there.”

read

read  see

see  read The Atlas Hypothesis — a technical briefing

read The Atlas Hypothesis — a technical briefing