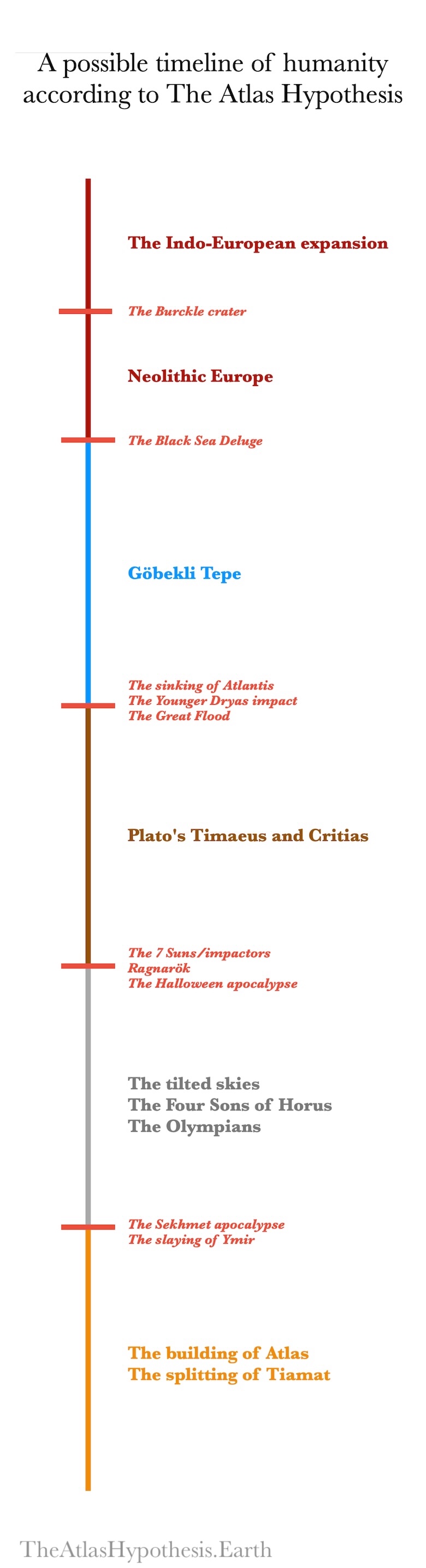

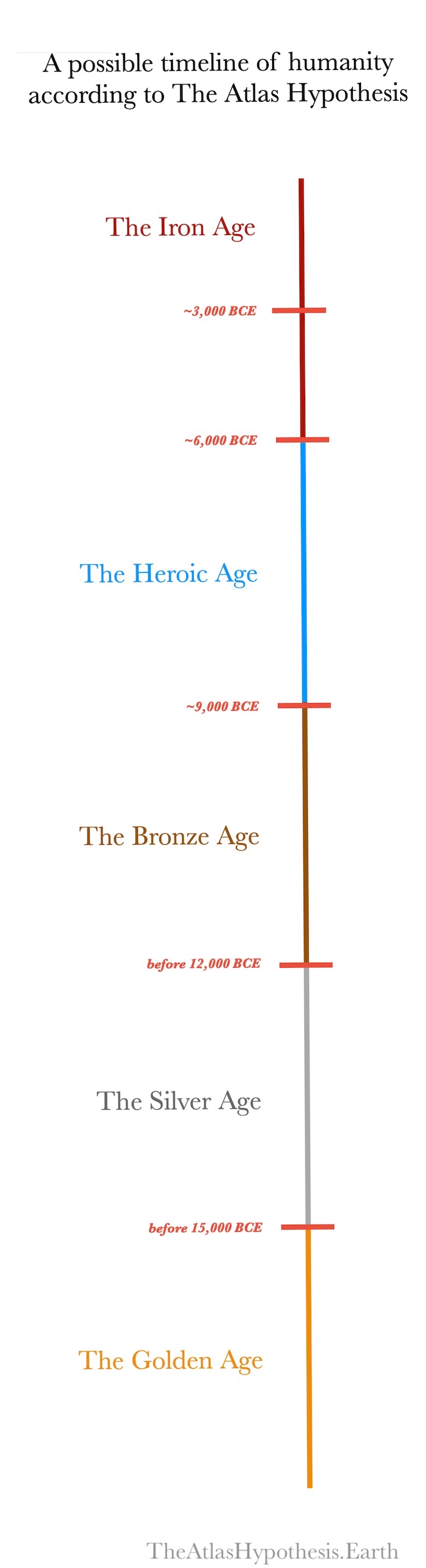

according to The Atlas Hypothesis

...before 15,000 BCE

The Golden Age civilization developed and reached its zenith. How long it had existed so far is irrelevant.

What is very important, however, is that they developed two technologies critical for this story:

- an incredible material from which they know how to make arbitrarily long yet unbelievably strong cables

- geoengineering at the level of manipulating the Earth's crust many miles deep

The eternity of the abyss

A giant comet enters the solar system, and after some time its fragments are captured in a resonant orbit that crosses Earth's own. It is recognized as a threat.

The swarm keeps fragmenting. It's impossible to steer the resulting debris away, despite the high technology available to the civilization at the time. It becomes a stream, and the planet no longer just approaches an orbit of another celestial body — the Earth now has to cross a highway, where some rocks, at that time, are miles in diameter.

Computer modeling fails at long time horizons due to outgassing and collisions, but it is already clear that within a few centuries, continuous fragmentation raises the probability of encountering a very large-scale asteroid to nearly 100%.

Work begins not so much to counteract as to mitigate the threat. Continuous bombardment by thermonuclear charges breaks down the biggest rocks — now they won't destroy a continent, just several cities. Shelters are built. The orbital habitats and space elevators are prepared for autonomous, closed-cycle existence for at least decades, while the impact winter lasts. Increasingly, it is accepted that an encounter with a giant block is imminent and unavoidable. Fragmentation attempts fail. The trajectory is predicted. The consequences are projected to be existential.

The impossible project

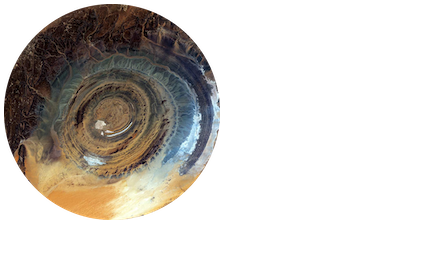

Among others, work begins on a very unique project. On the equator, a volcanic dome is induced (remember geoengineering?), and then a mile-scale ellipsoid capsule is placed inside, creating a shelter fully isolated from the environment. Tsunamis, earthquakes, acid rain, impact winters, air bursts — all of this will now happen somewhere else, out there. Is it the only plan? No. It’s simply one of many ideas.

The project is even more unique: on top of the capsule, a docking apparatus for accepting a space-elevator tether is attached. Now the capsule can be mechanically pulled upward while receiving energy via superconductive cables woven into the tether.

The problem of water supply is solved in a similarly unique manner. The capsule exists beneath the local aquifer; it taps into the same primordial waters as we do today — just from the opposite side.

Nourishment and waste? Let’s say biogenerators produce a drink similar to Huel, and grow meat reminding that of animals. Both are of much higher quality than anything you can have today — to the point where this kind of food becomes both medication and developmental supplement, massively extending healthspans.

The capsule plays several roles. It is divided into floors, each with its responsibilities. The lowest floors are the most interesting.

The seed of civilization

At the developmental level of humanity at that time, it is impossible to exist without automation. It is non-negotiable: the capsule must hold the latest technology and the best of human knowledge. Computer clusters with multiple layers of redundancy are placed on the lower floors, their memory banks filled with science, their circuits made of an indestructible material. The cluster is triple-redundant.

The compute is accompanied by the AGI of the time — digitized minds of the best humans who had recently lived — and several options for user interface: AR, mind synchronization, and human-to-human simulation. Of all three, we can only comprehend the last. The other two unlock bandwidth and entanglement of such depth and richness that a human brain cannot distinguish it from natural thought — only better.

Yet it is the second part of the civilization-restarting stock that is truly astonishing. Quite recently, humanity had learned how to preserve human bodies for decades, even centuries. A person could go to sleep in a sarcophagus and wake up a thousand years later. Increasingly large numbers of people chose this option when they found themselves sick with incurable diseases, or simply too old to enjoy life. An army of the hopeful was waiting for the bright future of even higher development to come and wake them — to welcome them into an even better world.

The megashelter employed the same technology. It had rows upon rows of beds of eternity, and a small army of the best engineers and scientists the Earth could provide sleeping in them. Also some politicians. And their kids. And a couple of friends. They weren’t hopeful for an unbelievably bright future. They knew that on the other side, a broken world awaited them.

What they didn’t know was that the destruction on the surface of the planet turned out to be much greater than anticipated. When they woke up, only a few crippled cities remained on the surface — and several million people survived in the orbital habitats.

Disaster strikes

When you're watching the planet from an observation deck at an unimaginable distance, the spectacle of death unfolds in slow motion. No sound from the all-destroying hurricanes reaches your ears. The tsunamis rising like walls, the screaming people — all of that is down there. You’d need a telescope just to see a megawave crushing the capital city.

A mile-scale impactor melts the ice caps. It’s still the Ice Age, mind you — the continents are covered in mile-thick glaciers.

The ejecta creates an effect similar to the one that boiled the dinosaurs: a curtain of material excavated by the enormous impact reenters the atmosphere globally, creating sauna-like conditions with non-stop massive rains that scrape the coastal cities — and the very soil underneath — off the bedrock.

The continental shelf we’re familiar with is flooded. Those coastal plains were home to hundreds of millions. All are gone.

Decades later, possibly a century

The non-sleeping shelter population had counted three generations now. A few thousand called the enormous capsule home. All they knew about the outside world was that it was chaos out there.

Outside, in some places, only a few survivors — with lifespans often not reaching their first grey hairs — had become cavemen. In other locations, a few cities were still grasping for civilization, which was slipping through their fingers.

One day, the shelter opened its doors. The new world awaited. A new humanity was born — out of the Cosmic Egg. They don't remember anything from the Golden Age — their world begins now. They're nourished and supported by a seemingly unending thick tether reaching into the sky — the infinite trunk of the World Tree.

The Silver Age began.

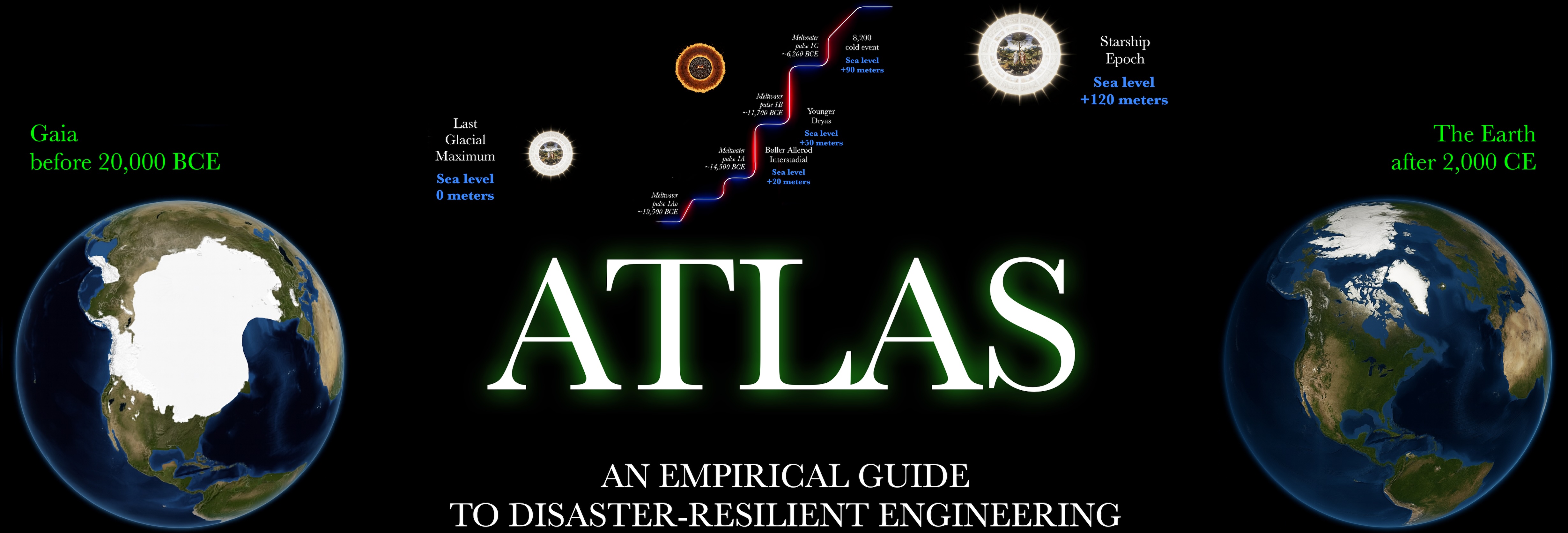

The Silver Age, The Second Sun

The tether of the space elevator had been damaged. The bombardment by the civilization-destroying swarm was so dense that two space habitats were lost — taking millions with them — and the planet’s main space elevator had its tether badly splintered.

Four other, smaller space elevators suffered their own hardships and, unwillingly but eventually, donated their tethers to the colossus. After all, they did not hold in their hands the lives of the best, nor the knowledge of all the past.

The titanic space elevator — Atlas, as they called it — now provided life-sustaining services to all the orbital platforms. For the surface population, it was a massive power cord; and the food factories placed on the counterweight — to improve mass distribution — sustained the humans below nutritionally.

It truly was Axis Mundi. The world rotated around it.

An unexpected turn of events

The population of the sarcophagi began to wake up. Yet they did not receive the welcome they had hoped for. Unacknowledged until now, the space elevator had a maintenance crew — someone needed to oil and clean the machines, to prepare and provide energy for the post-apocalyptic camps rising around the structure.

The half of the planet that had Atlas at its center now perceived it as a second sun — metaphorically, but also quite literally, because its microwave transmitters provided the energy they needed so badly. And the team maintaining and operating it held in their hands the destinies of the new world.

When the titans tried to resume their former roles, they discovered that those no longer existed. When they attempted to take control, a riot started almost immediately — the new world did not want to be devoured for breakfast by shadows from the past. They had lived for decades on their own — and they liked it this way.

Negotiations lasted months. Then years. Then decades.

In the end, a conflict erupted, and a radical decision was made — the governors and venerable academics from the previous life would go back to their sarcophagi and wait for their turn. Maybe.

The wildness within us

Humans being humans, and in the dire situation they were now living in — instincts took control. Cliques formed.

A gradient existed, however: those on the ground were quickly becoming... feral. Meanwhile, the space habitats — populated by the best and brightest before the cataclysm — did not experience such a massive drop in consciousness and self-control. Yet even they were now living almost like fiefdoms, with hierarchies and rituals.

The compute cluster presented a very unique and peculiar situation. Knowing very well how intelligence worked in general — not only in machines — the designers had predicted the degradation of the human side of the equation. It was right there, in the technical documentation:

- Active compute infrastructure resilience: baseline 2 cycles, limited by generational competence decay.

- Psychoengineered ritualization protocols with aggressive continuous behavioral vetting extend operational continuity by approximately +3 cycles (≈5 total), ~90% autonomous degraded-function capacity under kernel-module lockdown and system-console deactivation.

- Expected human-dependent SRE capacity attrition (all causes): ~20% per cycle.

The system didn’t just tell operators what to do — it enforced operational procedures, with humans explicitly acknowledged as an increasingly dangerous system-level risk.

The moral failure

It is difficult to comprehend time. Years flew by. Then centuries. Three thousand years passed. Humanity now numbered in the hundreds of millions. But there was a problem overshadowing every one of those millennia.

In this new world, the future looked pessimistic. When you live in the shadow of the future — which lies in your past — sustainability and slowing down decay become increasingly common choices. This nihilism was percolating through the new humanity. There was less intentionality, less conscientiousness — yet shoots of new green science were starting to appear.

The planet had been overused; all the low-hanging fruits of gold were gone — the metal of choice of the previous, the lost, the Golden Age. Now gold was hard to procure — yet the ancient machines had whole blocks made of it.

It was a strange world — yet it worked. Civilization slowly marched on. Until the next disaster struck.

The Cycles

The swarm slowly morphed into a few resonance-driven condensations — filaments of debris forming clouds of stones and pellets several orders of magnitude thicker — a cosmic shotgun blast of destruction.

As in music, the system found its tone — the note of oblivion, the lullaby of amnesia, the rhythm of death. Every three thousand years or so, Earth now crossed this cosmic highway at rush hour.

The world knew about this. The world was preparing. Yet what the world did not expect was the loss of Atlas.

A direct hit broke the tether again. The resulting loss of power and mechanical jerk cracked the walls of the shelter. Magma flooded the floors, burning everything and everyone it encountered, suffocating those it couldn't reach — the ventilation system no longer functioned, and the burning winds pushed death up like a piston of revenge that nature, finally allowed to act, imposed on humanity's best survival mechanism in history.

Living in the ruins

In the carcass of Atlas, atop the collapsed dome of the shelter, a group stood solemnly, remembering the lost — millions of lives. They had survived an apocalypse. Again.

And now descendants of the genius engineers of Atlas did what they always would do when encountering a problem — they built a workshop. They saved all they could from the still-accessible floors of the dead shelter. They organized the survivors. They collected all broken pieces of machines from the Golden Age — many being literally golden pieces, as they came from the age of abundance.

Through the simple optics of the common folk, they were gods. They built the first temple of the new world. They gathered the golden toys from the grass. They named their city to honor Atlas — the fallen titan — Atlantis.

Two sides of the same coin

The other side of the planet was luckier this time. Civilization survived because the million-strong cities were spared the fiery beatings.

News about the fall of Atlas caused mixed reactions. Some mourned the source of planetary order, the guardian of the common language, the coordinator of global trade. Others weren’t so sure it was a bad thing — the planet, half-tribal by now, did not appreciate the complexities of the civilized snobs.

And soon, the snobs’ opinions no longer mattered. The language they had all spoken before splintered, multiplied, and reflected in the shards the local traditions of the new populations born from humanity’s bottleneck. There was no longer planetary order or global trade, too.

Only a chain of tether port cities reminded the world of what had been lost — they called themselves Navels of the World. And the main one was the city of Atlas — Atlantis. Yet no longer would an umbilical cord connect the hills to the sky, Gaia to Uranus, the primitive Earth to the post-scarsity space habitats.

The Bronze Age began.

The bleaker shine, the lesser minds

At the farthest trailing edge of history, at the end of a decline lasting several humanities, Atlantis was but a usual empire. The first settlers were exceptional, and their starting position — catastrophic from the point of view of the previous ages — provided the new city with a strong foundation. Yet arrogance and opulence crept in. We all remember the decline and fall of the Roman Empire — this story transcends time and place, for humans are the same everywhere and every time.

The mundane part of history

So should it really surprise us that the age of Atlantis did not leave much behind? When the Great Flood arrived and wiped the temples and edifices off the map, only a story or two of a war fought between local states remained. The winds of time then dried the mud into sand, and the sandpaper of time polished the place where once an impossible structure had reached for the skies.

It is hard to believe now that it ever happened — and impossible to see from the ground. Yet if you look from space, the original home of the Titan, the carving on the grave reveals itself:

— the flat scar tissue of the broken root,

— the bedrock where the Fields of Reeds once whispered,

— the round lid now closed forever over the last refuge of the Golden Age — the ark, the shelter, the Cosmic Egg, the Mound of Creation.

— Al Kha ⵣ the author of The Atlas Hypothesis

read

read  see

see  read The Atlas Hypothesis — a technical briefing

read The Atlas Hypothesis — a technical briefing